Press

-

CBC Yukon

Actor and educator Michael Greyeyes discusses the growing prominence of Indigenous theatre in Canada, and what it's like to take on an iconic role in a recent Hollywood production.

-

Classical FM 96.3

Reviewed by Paula Citron

September 23, 2011

from thine eyes

Signal Theatre/Native Earth Performing Arts

Choreographed and directed by Michael Greyeyes

Written by Yvette Nolan

Performed by Sean Ling, Claudia Moore, Michael Caldwell, Ceinwen Gobert, Shannon Litzenberger and Luke Garwood

Enwave Theatre

Sept. 22 to 24, 2011from thine eyes is a beautiful piece of dance-theatre. Conceived, choreographed and directed by Michael Greyeyes, the work looks at characters from four different stories, who must come to terms with this life before passing on to the next.

Greyeyes and writer Yvette Nolan do not compromise in presenting raw emotions. We see a murderous junkie, an abusive husband, a couple who have lost a child, and a doctor and her A.I.D.S. patients.

The marvel is how the gifted Greyeyes can create narrative choreography – movement that tells a story and depicts character and relationships. Everything works in this piece – the text, music, set, costumes, lighting, and, of course, the compelling performances.

If I have one cavil, it is the ending. We see the doctor and her patients going into darkness, followed by a small flash of light. I needed to see all the characters going into the light to denote their passage.

Photograph by Scarlet O'Neill.

-

"I'm not interested in staging ethnicity"

PAULA CITRON

Special to The Globe and Mail

Published Tuesday, Sep. 20, 2011Michael Greyeyes has a restless nature. This could account for his peripatetic career: He has been a dancer, choreographer, actor, director and university professor.

All of this is taken into account in his epic dance-theatre piece from thine eyes, which opens the DanceWorks season at Toronto’s Enwave Theatre on Thursday. And all of those skills are put to use in the piece’s heavy theme – dealing with moving on from this life into the next.

“Because of Michael’s varied background, he treats the body as an instrument with exciting potential,” DanceWorks producer Mimi Beck says. “His robust movement vocabulary is linked with strong narrative ideas.”

Greyeyes, 44, is a Plains Cree who was raised in Saskatoon. The story of from thine eyes began in the 2008 Cree opera Pimooteewin (The Journey), for which he was both director and choreographer. The opera deals with a trickster and an eagle who visit the land of the dead to bring the spirits back to the land of the living.

He wanted to explore the topic in more detail. “Aboriginals people believe that a new consciousness is required for a new journey. We need new eyes if we are to move forward,” he says. “What truth do people see at the moment of their deaths? The title is from the Koran, ‘Lift the veil from thine eyes,’ denoting that new understanding.”

Greyeyes’s dance journey began when he joined his sister’s ballet class when he was 6 – and at the age of 9, he was accepted into the National Ballet School.

The family moved to Toronto so that their son could be a day student. “My parents gave up a lovely home and an ideal life in Saskatoon for a condo in Scarborough,” Greyeyes says. “They had both gone through the residential school system, and they were not going to have their son leave the family.”

But Greyeyes felt that he was “looking for more from dance.

“I had too big a brain for pliés,” he quips.

It was Karen Kain, now the artistic director of the National Ballet of Canada, who steered him to Eliot Feld’s company in New York, where he spent three years and met his wife, Nancy Latoszewski.

He became excited about acting when another Feld dancer suggested his name to a company that needed an Aboriginal dance choreographed for a play. “I liked the way actors ask questions, and go deep into character, role and intention,” says Greyeyes, who now teaches in the theatre department at York University in Toronto.

The scenes, dialogue and character development for from thine eyes come from playwright, director and dramaturge Yvette Nolan. Of Algonquin descent, Nolan was artistic director of Native Earth Performing Arts for eight years.

“The four stories that make up the dance theatre have different age dynamics and emotional states, but all the characters have to come to terms with this life,” Nolan says. “They remember things, which helps them to move on.”

The major characters are a murderous junkie, an abusive husband, a couple who have lost a child and a doctor who works with AIDS patients. Each story has its own elaborate set. The six performers (Michael Caldwell, Luke Garwood, Ceinwen Gobert, Sean Ling, Shannon Litzenberger and Claudia Moore), all carefully chosen by Greyeyes, are both strong dancers and strong actors. None are Aboriginal.

The question then becomes: If Greyeyes’s dancers are non-Aboriginal, and his choreographic métier is contemporary dance, where does his “Indian-ness” come into play?

His answer, in part, can be found in a scholarly article, "Notions of Indian-ness in Contemporary First Nations Dance," that Greyeyes wrote for a conference in 2009. He came to the conclusion that there is no Aboriginal dance per se, only dance by Aboriginal artists.

“I’m not interested in staging ethnicity. Indian-ness as a concept is evolving and expanding. My Indian-ness is based on Indigenous principles like the storytelling tradition,” Greyeyes says. “My theatrical exploration deals with what matters to first nations as a community. Governance, or the way we treat each other, is also important. I may be the director, but everyone has a voice.”

While Greyeyes and Nolan have different Aboriginal backgrounds, in the rehearsal room they developed their own cosmology, or set of rules, that sprang naturally out of their joint native existence. “We share the same world view,” Nolan says. “We believe that we are all connected, and responsible for each other. Indian-ness is not just a beads and buckskin show or a powwow. The Indian-ness comes out of us. We don’t leave our Indian-ness at the rehearsal-room door.”

Greyeyes says: “My work embraces what the elders believe and the values I was taught.”

from thine eyes is the first live production in Canada to have its carbon footprint tested. “York University’s theatre department is keenly interested in bringing environmentally sustainable practices into theatre,” Greyeyes explains. “Last year, I was asked if from thine eyes could be used as a pilot project for exploring how to make greener productions.” The set designers have made ecologically sound choices in construction materials, glues and paints, recycled natural fabrics and dyes, and LED lighting technology, he says. “I was very excited by the project.”

Photograph by Cylla von Tiedeman.

-

Carriage

In rehearsal

Filmmaker and dance artist Michael Caldwell interviews Nancy Latoszewski prior to her performance of Carriage at the iconic Toronto dance series "Older and Reckless"

-

The Toronto Star

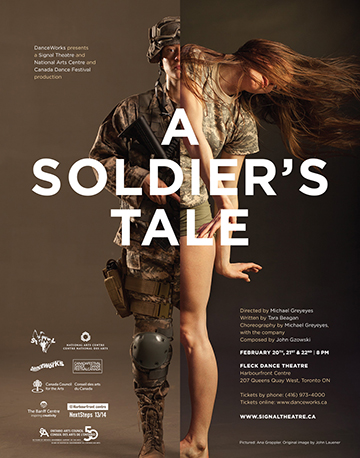

A Soldier's Tale hybrid approach to a harsh wartime tale

By Michael Crabb

Michael Greyeyes was never a soldier, but he’s done plenty of fighting.

The Saskatchewan-born, National Ballet School-trained dancer turned actor has portrayed native warriors such as Crazy Horse and Tecumseh and, more recently, 20th-century soldiers. Greyeyes, 46, a Plains Cree from the Muskeg Lake First Nation, has even experienced the rigors of boot camp in toughening himself up for such roles.

It’s one reason Greyeyes, a theatre professor at York University and founder/artistic director of Toronto’s Signal Theatre, is making soldiers the focus of the multi-disciplinary company’s latest production, A Soldier’s Tale.

Specifically, the work examines the enduring psychological toll that ripples out from a soldier’s wartime experience to engulf family and friends. Officially named Operational Stress Injury in the Canadian Forces, its consequences can range from alcoholism and spousal abuse to severe emotional disorders that have too often led to suicide.

“My film work has given me empathy for what soldiers go through,” explains Greyeyes, whose own father served in the Canadian Armed Forces during the reconstruction of Germany after the Second World War. But Greyeyes’ native heritage has also played a part.

“Growing up within the Cree culture, at every gathering we honoured our veterans. It was simply part of what we did, just as some people say grace before a meal.”

Even a modest estimate suggests one in three able-bodied, service-aged native men enlisted in the Canadian forces in the First World War and have similarly volunteered in every subsequent conflict in which Canada has been involved, right up to Afghanistan. Many, from remote communities, found themselves serving thousands of miles from home, a circumstance referenced in the lyrics of “Soldier Boy,” an honour song often performed at native gatherings.

Its words gave Greyeyes and writer Tara Beagan, co-founder of newly formed Indigenous theatre company Article 11, the starting point for Act I of A Soldier’s Tale, which revolves around a fictional character, John Joseph, played by actor Keith Barker.

The action takes place in Saskatchewan as soldiers return from the Second World War. The second act of the 90-minute production jumps six decades to the age of the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts, where the clear-cut, good-versus-evil drivers of earlier wars became morally muddy. Yet, different though wars may be, the soldier’s experience — the fear, the struggle to survive, the residual guilt — remain constant.

In keeping with Signal Theatre’s hybrid approach, the 13-member cast includes actors and dancers, and the production intermingles spoken word, music and movement.

Despite their extensive research, including interviews with veterans, Greyeyes and Beagan decided not to relate specific personal stories.

“Indigenous protocol dictates that you don’t change someone else’s story,” says Greyeyes. “We wanted the freedom to make certain dramatic choices, so everything is fictionalized.”

Even so, Act II was inspired by the story of Hopi Indian Lori Piestewa, slain during the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq. “We felt it important to follow a female soldier,” says Greyeyes.

He also wanted to underline the impact on families — Piestewa had two children — and has incorporated his and wife Nancy Latoszewski’s daughters, Eva, 11, and Lilia, 9, into the fabric of A Soldier’s Tale.

“Kids bear the costs of war particularly harshly,” says Greyeyes, “so we wanted children involved.”

The decision necessitated much careful explaining as Greyeyes and Latoszewski prepared their children, both devoted ballet students, for participation in a work that deals with disturbing adult material.

Greyeyes would like A Soldier’s Tale to raise awareness of an issue that for too long has been ignored. In awareness, he says, there is also a thread of hope.

Ultimately, says Greyeyes, “This is a work that honours soldiers and their experiences.”

Poster Image desiged by ALSO. Original Photography by John Lauener.

-

Almighty Voice and His Wife

note: Artistic Director, Michael Greyeyes directed an important re-staging of Daniel David-Moses' seminal play for Native Earth Performing Arts. This production toured across Canada, including the 2012 PuSH Festival in Vancouver. This collaboration marked an important stage in the professional relationship between Greyeyes and Nolan, who is now an integral part of Signal's creative team.

PERFORMANCE, PLACE, AND POLITICS

A BLOG ABOUT THE LOCAL/GLOBAL INTERFACES OF AUDIENCE AND EVENT.By Peter Dickinson

THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 2, 2012

Push 2012 Review #11: "Almighty Voice and His Wife at The Waterfront"

As PuSh Festival Senior Curator Sherrie Johnson and I were discussing last night after the premiere of Daniel David Moses' Almighty Voice and His Wife at the Waterfront Theatre, it's hard to believe the piece was written and first premiered way back in 1991. That's how theatrically audacious and representationally daring the piece is, made even more so in this compelling production from Canada's premiere Aboriginal theatre company, Native Earth Performing Arts, which is here vividly directed by Michael Greyeyes in a co-presentation with Touchstone and Pi Theatres as part of this year's Aboriginal Performance Series at the Festival.

The play is a two-hander told over two acts and based on historical incidents. Almighty Voice is a Cree man from the One Arrow Reserve in Saskatchewan who is arrested after poaching a cow. He escapes from prison and a manhunt is initiated by the Northwest Mounted Police. Hiding out at his mother's home with his wife, White Girl, who has already had a terrifying vision of his demise, Almighty Voice prepares for the inevitable shootout. When it comes, it is brutal and bloody. All of this is told in a fairly straightforward manner over 10 compact scenes, the titles of which are announced in a Brechtian manner by White Girl. However, this metatheatrical conceit--together with the almost deliberately anthropological/dioramic way (most of the scenes are played in a single large centre spot on an otherwise bare stage) this "true story of the dying Plains Indian" is staged by Greyeyes--is a clue to what's coming next.

Indeed, returning from intermission the audience discovers the stage now cluttered with props, the flies open to expose the wings, and a cue card dangling from the rafters announcing Act 2: Ghost Dance. The actors themselves, we soon discover, return in white face, with White Girl now additionally dressed like a Mountie and, true to the interlocutor/impresario role she now takes on, charged with getting the person she addresses as Almighty Ghost to perform his Indianness for us. Combining aspects of the vaudeville routine and the minstrel and medicine shows, the second act is a series of increasingly outrageous and high-stakes riffs on "redskin" stereotypes, addressed directly to the audience. Indeed, in Act 2 Moses doesn't just break the fourth wall, he explodes it, with both Mr. Interlocutor and Almighty Ghost coming out into the audience at various points, and each strategically playing to and upon our ideological sympathies in order to gain the upper hand.

And it is this last point that makes Moses' play at once so groundbreaking and compellingly contemporary, for it accomplishes via its canny structure the double task of exposing both real and representational violence to us, theatricalizing Aboriginal stereotypes and then catching us in the act of succumbing to them. It is risky material, to be sure (think of some of the backlash and misinterpretation that accompanied Spike Lee's film Bamboozled), and it takes very accomplished performers to bring it off successfully, capturing both the ironic comedy and the tragic drama underlying the jokes. Happily, the incredibly talented Derek Garza and PJ Prudat are more than up to the task, and kudos must go to all the artists involved in bringing this masterpiece of Canadian drama back to the stage.

Photograph by Red Works/ Nadya Kwandibens.

Signal theatre communiqué

This space serves as a forum for the artists of Signal to blog about the work we are pursuing, both as a company and as individuals. It is a place to speak about the politics that drive our work and affect our lives in innumerable ways. We invite you to join us to read about the art that we all care about.